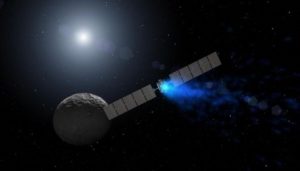

With no fuel left to point its antenna at Earth, NASA's Dawn mission to explore Vesta and Ceres has reached its conclusion after 11 remarkable years in space.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

It has been an amazing ride. Short on fuel and now stationed in permanent orbit around dwarf planet 1 Ceres, the end has come for NASA's Dawn spacecraft.

"Today, we celebrate the end of our Dawn mission," said Thomas Zurbuchen (NASA HQ) today in a press release. "The astounding images and data that Dawn collected from Vesta and Ceres are critical to understanding the history and evolution of our solar system."

NASA engineers have said that the spacecraft, now depleted of fuel, will remain in a final elliptical orbit of just over 27 hours in duration, reaching a most distant point (apoapsis) from Ceres of 2,485 miles (4,000 kilometers) and a closest periapsis approach of 22 miles (35 kilometers). This is in line with planetary protection protocols, guaranteeing Dawn won't crash into Ceres for the next few decades.

“Dawn's legacy is that it explored two of the last uncharted worlds in the inner Solar System,” says Marc Rayman (NASA-JPL) in a recent press release. “Dawn has shown us alien worlds that for two centuries were just pinpoints of light amidst the stars.”

The spacecraft missed two scheduled communications with Earth on October 31st and November 1st, leading mission scientists to conclude that the spacecraft had finally run out of fuel. Dawn will now remain permanently in orbit around Ceres, a testament to the pioneering spirit of space exploration. There were early proposals for a third flyby mission to asteroids 2 Pallas or 145 Adeona in 2019, which were scrapped in favor of remaining at Ceres for further exploration.

Dawn performed several firsts in space exploration: It was the first and only mission to visit both Vesta and Ceres, NASA's first deep space mission to use ion propulsion, and the first mission to orbit more than one target body beyond the Earth and Moon. Dawn was also the first mission to visit a dwarf planet, beating out New Horizons by just a few months, which made its historic flyby past Pluto and Charon in July 2015.

The problem comes down to a lack of hydrazine. Dawn's reaction wheels used for pointing the spacecraft failed earlier in the mission. Though the spacecraft uses three xenon-fueled ion engines for its main source of propulsion, its maneuvering thrusters depend on hydrazine. Without steering, Dawn will no longer be able to aim its main communications antenna back at the Earth.

A Thrilling Saga of Space Exploration

Launched atop a Delta II rocket from Cape Canaveral Air Force station on September 27, 2007, Dawn required a series of long burns of its ion engines to slowly get up to speed. Dawn also performed a Mars flyby on February 17, 2009, giving engineers a chance to calibrate cameras and instruments en route to its main objectives in the asteroid belt.

NASA/JPL/MPS/DLR/IDA/Dawn Flight Team

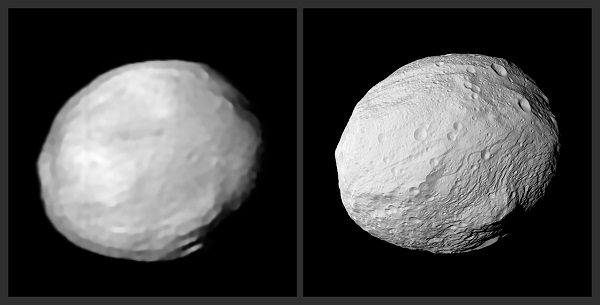

Dawn arrived at 4 Vesta on July 16, 2011. Dawn revealed the misshapen world of Vesta in dramatic detail, mapping it from pole to pole while probing it from core to surface. One key finding from Dawn at Vesta was that it seems to be the last of its kind, a remnant of the rocky planetesimals from the early days of the solar system.

ESO/L. Jorda et al., P. Vernazza et al.

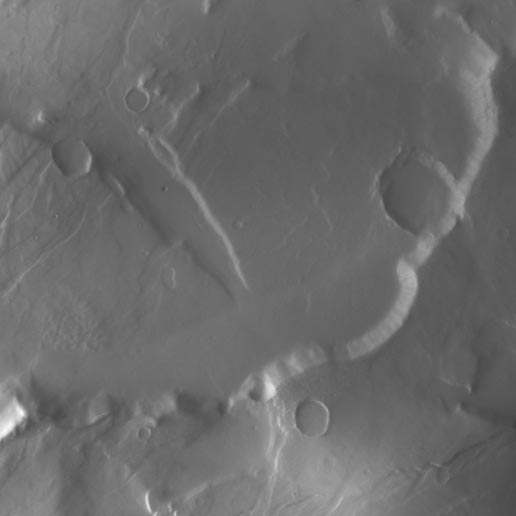

Dawn then fired up its ion engines and departed Vesta on September 5, 2012, for a 30-month transit, arriving at Ceres on March 6, 2015.

It turned out that the earlier exploration of Vesta was just a prelude for the excitement to come. On approach to Ceres, Dawn spotted several anomalous white patches on its surface. These proved to be briny salt deposits of hydrated magnesium sulfate and ammonia-rich clays, remnants of water eruptions from the world's interior.

Dawn gave us key insights into the cryovolcanic activity erupting on the surface of Ceres and a look at an active dwarf planet. Between Ceres and Vesta, Dawn explored about 45% (nearly half) of the mass of the main asteroid belt. Not bad!

“Although it will be sad to see Dawn's departure from our mission family, we are intensely proud of its many accomplishments,” says Lori Glaze (Planetary Science Division-NASA HQ) in a recent press release. “Dawn's science and engineering achievements will echo throughout history.”

The end of Dawn is just one of many endings in modern deep space exploration. Cassini wrapped up a decade and a half of exploration of Saturn last year on September 11, 2017. New Horizons will explore the Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule on New Year's Day 2019 on a brief flyby before heading out of the solar system. And NASA's Juno spacecraft will finish up at Jupiter once it succumbs to radiation damage accumulated on successive perijove passes, probably in 2019.

Sadly, our eyes in the outer solar system are going dark. NASA's Europa Clipper in the 2022 to 2025 time frame, and perhaps one or a pair of Ice Giant Orbiters headed to Uranus and/or Neptune in the 2030s, will likely be the next outer solar system missions on the launch pad.

It's truly #DuskforDawn, and you can follow the final days of the mission via the same Twitter hashtag. It has been an amazing 11-year mission. Dawn has given planetary scientists key insights into the formation of the early solar system and data to pour over for years to come.

0

0

Comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.